Cascade Party

A new path in Washington State politics.

A new path in Washington State politics.

Environment

Consensus across political spectrum for local control.

By Megan Blackburn Friend (November 13, 2025)

When Wahkiakum County Commissioner Dan Cothren opened the October 15 public meeting about a new community forest, at the Johnson Park building in Rosburg, with the words “This is not a park,” it caught my attention right away. It set the tone for the evening.

About forty people filled the room for the public meeting. I recognized people from the right, center, and left of the political spectrum. Judging from the questions and lack of rancor, people seemed to have an open mind about the proposal.

I wanted to know how Wahkiakum County would benefit, how the money from timber sales would be used, and whether this was just another version of industrial forestry with a friendlier name.

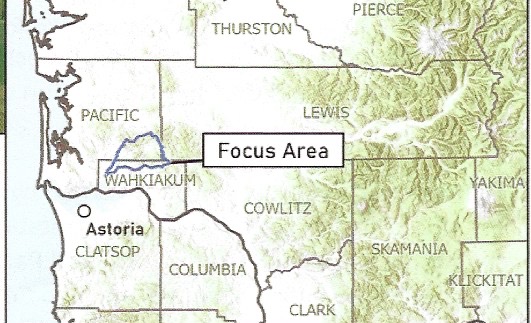

The project lies in the upper Grays River watershed, about twenty miles east of the Columbia River between Rosburg and the Willapa Hills. The focus area includes a mix of private timberland, conserved tracts, and Department of Natural Resources holdings.

The exact acreage for the plan is not specified, but related projects have conserved land in the Grays River watershed, including a Columbia Land Trust project that acquired approximately 537 acres and a separate conservation effort that conserved 1,103 acres.

The first phase of the Upper Grays River Community Forest is expected to cover several hundred acres, depending on available funding and land prices, with room to grow as more parcels become available.

This land drains into salmon, steelhead, and wildlife habitat that has seen decades of short-rotation clear-cuts. Those practices have compacted soils and sped runoff into the river, carrying silt that clouds the water and settles into spawning beds. The result is faster flooding and poorer habitat for fish.

The community forest model aims to slow that runoff, improve water quality, and restore balance to the watershed while keeping the land in working forest use under local control.

This project isn’t about playgrounds or picnic shelters. It’s about timber, public access, wildlife habitat, and whether local people will have a say in how our forests are managed.

Public ManagementThe plan is for a Public Development Authority (PDA). This authority will consist of two county commissioners representing Pacific and Wahkiakum counties respectively, two citizens chosen by those commissioners, and two people representing the Columbia Land Trust.

There are many community forests established in our state.

Commissioner Cothren made it clear that he sees the PDA as a way to bring timber revenue back to Wahkiakum County. He pointed out that most of the timberland in the region is now owned by large investment firms and timber companies Rayonier and Weyerhaeuser. Land is also owned by German companies. Cothren even mentioned an ownership connection with the European Union.

There used to be maps showing open timberlands, with roads hunters and families could use to reach places for elk, bear, mushrooms, and butterflies. Now, gates and locked access points have shut the public out. As one person said, “We’re left fighting over scraps.”

That frustration came through clearly. Everyone in the room seemed to agree that the current 35-year logging cycle is too short. It doesn’t allow for diversity or long-term forest health.

Flooding and Forest HealthSeveral people at the meeting noted that past logging on 30-year rotations has worsened flooding in the lower river. Clear-cuts and compacted soils speed runoff, while shorter rotations limit root systems that stabilize slopes and retain water. The proposed community forest model, with 55 to 60 years harvest cycles and variable-density thinning, could help slow runoff and improve watershed health.

Slow GrowI spoke with Austin Tomlinson from the Columbia Land Trust. He explained that if the Land Trust purchases land first, they would hold it only temporarily until the PDA is ready to take ownership. The long-term goal is for the PDA to hold title and manage the forest.

Austin also confirmed that the amount of acreage in the first acquisition will depend on land prices and available funding, with purchases focused within the general upper watershed area outlined on the map presented at the public meeting. He expects the PDA charter to be approved by the counties before the end of the year, noting that Columbia Land Trust’s board has already given its approval.

Forest management decisions, including harvest schedules and revenue distribution, will be made by the PDA board with input from foresters, funding partners and the public.

Austin also described their approach to what’s called “variable density thinning.” Instead of clear-cutting, about a third of the trees would be removed to create space for growth and diversity. The healthiest trees would remain, snags would be left for wildlife, and species like cedar and spruce would be planted to restore balance.

Hearing that gave me some optimism. It’s not preservation, but it’s a step toward responsible management.

Public Development AuthorityAfter the meeting, I also heard from Beth Johnson, the administrative clerk of the county board of commissioners. She confirmed by email that the PDA will be created by ordinance, after a public hearing, and that the interlocal agreement and charter will be available for public review. That means there will be a chance for citizens to weigh in before anything is finalized.

All PDA meetings will be open to the public, with time for comment and input, and the board will include commissioners from both counties.

Another leader is Sandra Staples-Bortner, a resident of the Upper Elochoman Valley. Sandra and her husband moved to the area a few years ago, and she’s been active with the Marine Resources Committee and other local groups. Before relocating here, she served as the Executive Director of a land trust in northern Washington, giving her experience in community forest and property acquisition efforts.

There are still questions to answer about public access, how timber revenue will be used and distributed between the counties, and how the board will ensure that citizens are truly represented.

The idea of a community forest won’t bring fast rewards. We won’t see major public revenue for decades. But it’s an investment in the future, a way to restore local control, rebuild trust, and make sure our children and grandchildren inherit a forest that’s alive, healthy, and cared for.

By Megan Blackburn Friend lives in Wahkiakum County. She is a contributor to the Wahkiakum County Eagle.

👉Grays River Community Forest Flier.pdf