Cascade Party

A new path in Washington State politics.

A new path in Washington State politics.

Unsheltered

Walla Walla Alliance for the Homeless

By Johann Peters; (September 22, 2025)

In a city synonymous with incarceration; local government, community groups and residents work together to provide stability, hope and a path towards independence for people struggling with homelessness and addiction.

Walla Walla, Washington is known for its thriving vineyards, considered among the best in the world, with a restaurant scene built around pairing Columbia Valley wines. At the same time, Walla Walla is also home to the state penitentiary, located just over a mile from downtown.

While in Walla Walla, I was fortunate to meet Jordan Green, Executive Director of the Walla Walla Alliance for the Homeless (WWAH). The word alliance is key here — this isn’t just a shelter, but a coalition including the City of Walla Walla, community partners, and local residents working together to provide stability and hope.

Green is also currently running for City Council in College Place, a neighboring community. Before his nonprofit work, he was a manger in the automotive industry in Portland. Green relocated to Walla Walla, continuing management in the automotive industry.

WWAH operates on a lean budget of about $700,000 a year. Its shelter site is on land provided by the City of Walla Walla, located right next to the state prison. With a staff of seven, along with many volunteers, the organization provides structured recovery in three phases.

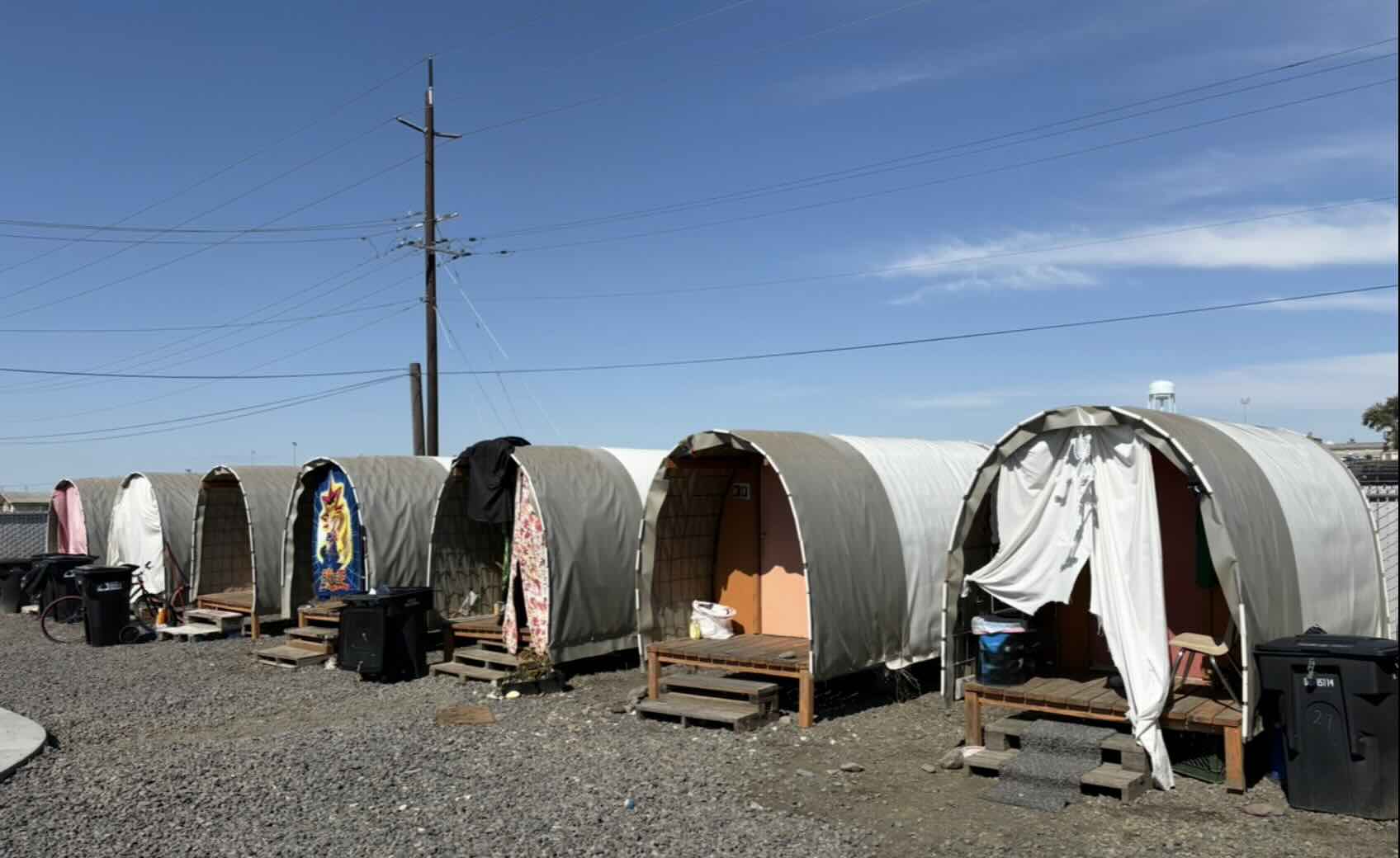

The first phase begins in a low-barrier quonset hut. Participants sign a rules-based “good neighbor” agreement — no substances, respectful behavior[1] — and are directed toward services to start addressing life challenges.

The site includes an optional classroom for life skills and job retraining, two full-time peer counselors available Monday through Friday, 24-hour security, a housekeeping staffer (a former resident), a handyman, and Jordan himself — who oversees compliance, expansion projects, donations and volunteer coordination.

Security is emphasized not just for order, but for behavioral health support and crisis de-escalation. Meals are provided creatively; local churches each cook one dinner per week in their approved kitchens, while breakfast and lunch are typically “grab and go” donations from Starbucks, Safeway, local bakeries, and other businesses.

The second phase is a step up into tiny houses. Here, participants get serious about rebuilding their lives.

Mandatory classes and stronger engagement with services are required. This is where the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program often comes into play. LEAD, launched in Walla Walla in 2021 as the first of its kind in Eastern Washington, diverts people with unmet behavioral health needs away from jail and into services. It is a collaboration among Comprehensive Healthcare, Blue Mountain Heart to Heart, local law enforcement, prosecutorial partners and the City of Walla Walla.

The third phase is offsite re-entry, with participants moving into independent living and rejoining the workforce. Green described the shift from phase one to phase two as “kind of like purgatory” at first — hard and uncertain — but with the light at the end of the tunnel beginning to appear. He’s realistic, acknowledging that some individuals with severe mental illness may never fully stabilize and will require wraparound services or group homes. Still, he’s hopeful, stressing that WWAH can at least assess people, stabilize them, and start them on a path forward.

Green says, people often complete a 7-day detox and feel better but many don’t continue on to 30-day or longer rehab, which he believes is necessary for real recovery. This is a shame as the LEAD program wants to lead folks away from incarceration. The state penitentiary is synonymous with Walla Walla — and it's ominous how people can discard the opportunities WWAH offers.

The results WWAH achieves on just $700,000 per year are striking. Through focused donations and volunteer support, along with the partnership of the City of Walla Walla, they’ve built what I consider a low-cost, high-value model — balancing accountability (“sticks”) with incentives (“carrots”), while restoring dignity and self-worth.

The work of Jordan Green, his staff, the volunteers and the City of Walla Walla deserves recognition. It’s an example of what can be done when nonprofits, cities and community members pool resources into a cooperative, centralized clearinghouse model. It’s not rapid or flashy, but steady and effective — offering stability first and then gradually supporting growth.

In my view, this is a model worth replicating elsewhere. It represents the best of what happens when accountability, encouragement, and community come together to help people rebuild lives.

[1] Walla Walla Alliance for the Homeless Policy:

Who can stay at the shelter community?

We accept anyone over the age of eighteen who needs shelter and can obey the rules as long as we have vacancy. We are “barrier free,” meaning that we do not exclude those who use drugs or alcohol outside of the shelter community as long as they can follow the rules and not be disruptive to others. Drugs and alcohol may not be used on site.”

Johann Peters lives in Cowlitz County. He serves on Cascade Party board of directors in position 3/6.

(Image: Johann Peters)